Every time I rode the sky train past Siam, a big sign at BACC advertising Nurture Gaia exhibition always caught my eye. The gigantic soft pastel signature stood out against the backdrop of everyday life. Because I had nothing better to do on a Sunday, I decided to go. Like the sign, the event seemed too big to miss. On the official website, it claimed to house over 100+ artworks from 33 artists from multiple countries. Surely, there would be something for me.

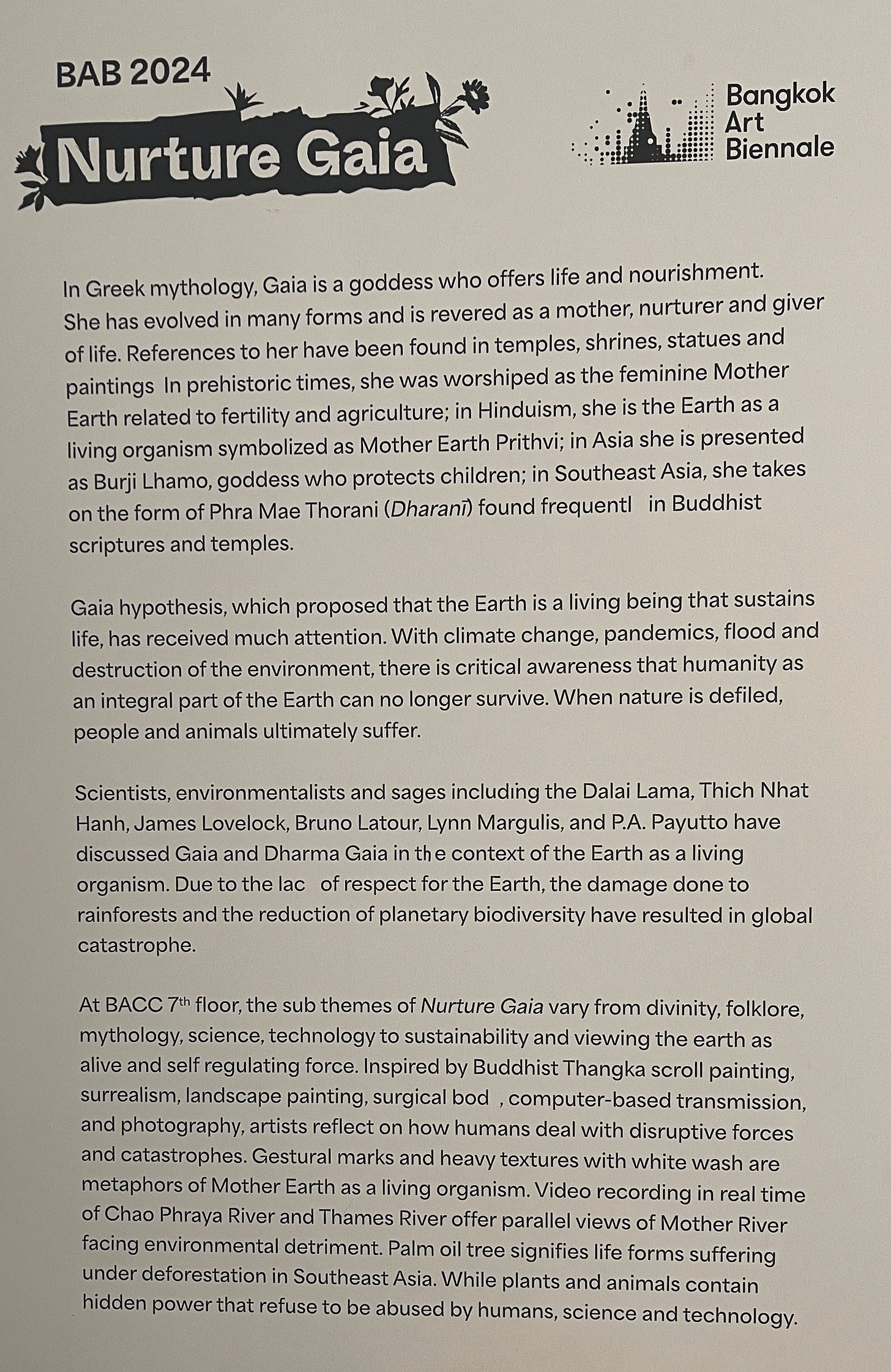

My interest was only mildly piqued, when I read the exhibition statement on the 7th floor. Nurture Gaia was defined by a simple narrative. Mankind degrades the Earth / Mother Nature / Gaia, and they will to suffer because of it. It was a long way of saying on this floor the arts were about about conservation and sustainability.

On the 8th floor, Nurture Gaia focused more on Gaia. The theme shifted from sustainability to gender. I took one gender study class in university, so I was somewhat excited. But the exhibition was a let down. The artworks mostly spouted traditional values of femininity and motherhood. Moreover, the blurb obstructed, rather than assisted, the enjoyment of many works.

I - The Blurb

My issue with the museum started at the very beginning on the 7th floor. Some letters in the museum statement were missing. (see IMG 1) Lack became lac. Frequently became frequrntl. Body became bod. The text overall was still comprehensible. But if this was at the beginning, then what could be next?

(Edit: On 25 Jan, I rechecked the exhibition again, and the museum statement had patched up. When I visited for first time on 23 Nov and the second time on 1 Dec, the letters were missing)

On the 8th floor, the gallery statement thankfully contained all the letters. Instead, the issue of the gallery text spread to each artwork blurb. During my visit, the blurb hindered the art, rather than assisting it.

Some works did not have any blurb dedicated to it. Such precious space was only reserved for boosting the artist. When I read the blurb for Luminaries Moon (2023) and Untitled (1986), I only knew who Prasong Luemuang is. I knew he is inspired by Buddhism. I knew where his work was exhibited, what award he won. Still, I did not know why his art was hung alongside the two lingas displayed at the opposite of the painting.

Lumainaries moon was explained in the BACC TikTok. It is largely similar to a write up of his solo exhibition ECLIPSE where the two artworks were previously shown. When I asked the museum volunteers, she said the two painting was interacting with one another. The women was a heavenly creature looking into human world (museum visitor) via the eye. But that room was not always packed. So, does that means she often saw a pair of penis instead?

Some blurb did not provide enough context for the artwork. Busui Ajaw painting depicted Amamata from the Ahka folklore. The blurb wrote that she was “the revered first mother and goddess-like figure embodying fertility, childbirth, and the protection of women.” Then, it went on to interpret the work without revealing the Amamata story. “Ajaw explores the theme of motherhood, ancestral connection, and the unwavering strength and resilience of Akha women.”

Of course, many questions arose. Who was Amamata? What was her story? Why did the rawness of this painting related to motherhood? How did the painting of a monster devouring a man connect to being a mother? I only knew her story, when I was googling around writing this review. At the museum, I could only blindly follow the museum words without asking any question.

(The answer: At the beginning of time, god was giving away the seed of woman. Akha people were late, so they did not receive any. God told them to sing on their way back, and whatever they caught would be the seed. Amamata was a titan. When she heard the song, she tried to capture and eat Akha people. She lost, and was caught by the people. She gave birth to mankind and ghost-kind. From the legend, she also ate her six husbands. Because Ahka people spread their knowledge via oral tradition, Ajaw painting is one of the few piece of visual representation of Akha culture)

Not all blurbs was badly written though. The blurb of an uncomplicated works did a fine job. Daniela Comani 's YOU ARE MINE, for example, was a simple social experiment. The gender of the domestic violence victim and perpetrator was switched to highlight how common it was. Victim-Women. Perpetrator-Men. Switch. End of story. The blurb even gave an extra context. “[In Thailand,] 75% of cases of domestic violence are against women,” it wrote.

Unfortunately, most of the blurb were simply not good. After the first visit, I knew I had to come back, and googled each work individually. On the second visit, I sifted through the loads of information while standing among the crowd. It was not a pleasant experience, but it raised my appreciation of each work.

(Edit: There is also a activities booklet available in my visit on 25 Jan. Unlike the blurb, the booklet focused more on the artwork than the artist. Still, it did not give much content.)

The booklet activities included DIY palad khink, and asking “What is it [this piece of art] called, and who created it?”[the answer: Janus in Leather Jacket by Louise Bourgeois]1 and “There’s a feminine element hidden in this room that is not a work of art. Can you guess what it is?”. The answer: “The red wall. The red paint used on the wall in this room is called “Feminist Power.”2” But is feminine and feminist different?

Most the pages were giving question, or activities to boost viewer engagement. Much like the social media the inspiration of this booklet, the engagement seemed so surface-level.)

II - Mother

On the 8th floor, the gallery statement started with Gaia. She was “mother, nurturer, healer and giver of life.” You might think on this floor the exhibition was about the namesake god. But that was wrong. The statement was a catch-all to include any artworks about motherhood, feminine, or woman. But this was not completely true either. Political arts and a few ecology arts also showed up. Gimhongsok’s Solitude of Silences (the sculptures expressing the frustration of labor in the late-capitalist era) was here. The Last Resort by Latai Taumoepeau (a video performance expressing the displacement of the Pacific Island community from the rising sea level) fitted better in the 7th floor where the theme was sustainability.

But most of the works on the 8th floor followed the gallery statement. They were the same old story of motherhood that we had seen a million times before. They were feminine. They protected. They were dedicated. They were selfless. These works seemingly supported one another without any contrast, rendering the experience to be smooth and boring.

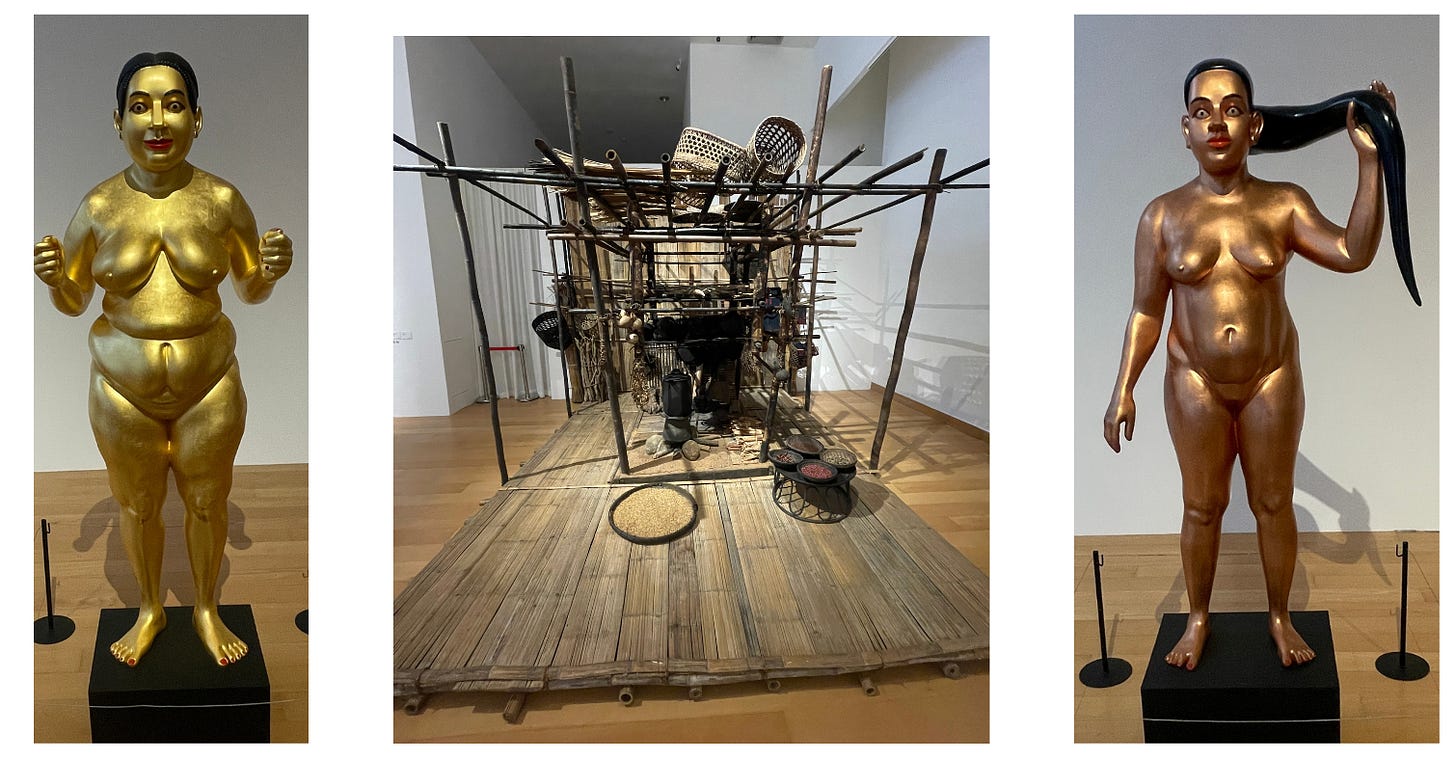

The first mom piece was Nature Study by Louise Bourgeois. (1984) (“the mother as dog-goddness3 and protector.”) Then, Jennie Bringaker sculptures. The Three women who hugged and protected her objects of affection. (Passenger (2023), Lineage (2023), Surfacing (2023) Then, Amanda Heng. A photographic portrait series of her and her mother taken over the period of 30 years. (Always by my side (2023)4) Then, Busui Ajaw presented two pieces. A series of paintings of Amamata, god of fertility, and a literal kitchen as the portrait for the mother. (Amamata the First Mom5 (2023), Ama Mijapu (mother’s kitchen) (2024)) By the time I read Ravinder Reddy blurb ("Her study child-bearing hip … [her] swollen child-birthing belly"), I rolled my eyes. (Woman tying her hair (2010), Woman holding hair (2010-2011), Bangaruamma (2011-2012))

I thought jokingly about how the museum should place Michelle Obama quote— 'Women and girls can do whatever they want. There is no limit to what we as women can accomplish.' —just for balance.

It did not mean that I thought the works were bad. Some pieces stirred some big emotion from within. When I saw Heng expressing the love between her and her mother, I was touched. When I saw her hugging her mom, I wanted to go home and hug my mom too. Nature Study unashamed display of breast and penis also drove me to think about sexuality intellectually. Why were we so afraid of sex it seemed to ask.

But, all together many works felt the same. There was no work that tried to challenge the concept of motherhood at all. In Sex and the City, Miranda faked a sonogram. When Miranda saw the image of the baby in her belly for the first time, her doctor expected her to be joyful for the incoming motherhood. But, she didn't feel it. So, she faked it. Her joy only came later in that episode, when she felt her baby kick. Even in the 90s, the series was somewhat skeptical about the myth of motherhood.

Conversely, the exhibition here did not question. These works did not explore the fear of being a mom. They did not investigate the feeling of failing at being a mom. They were just moms.

III - Politics

Meanwhile, the other works that tried to challenge the state quo were fine. Daniela Comani's YOU ARE MINE switched the gender of domestic violence. Men became the victims and the women became the perpetrators. The point is to reflect on the absurdity of domestic violence. However, don’t we as a society already have enough of this reflection? The knowledge that husband kills wife is not a new idea for anyone who listens to true crime content, or read any crime novel.

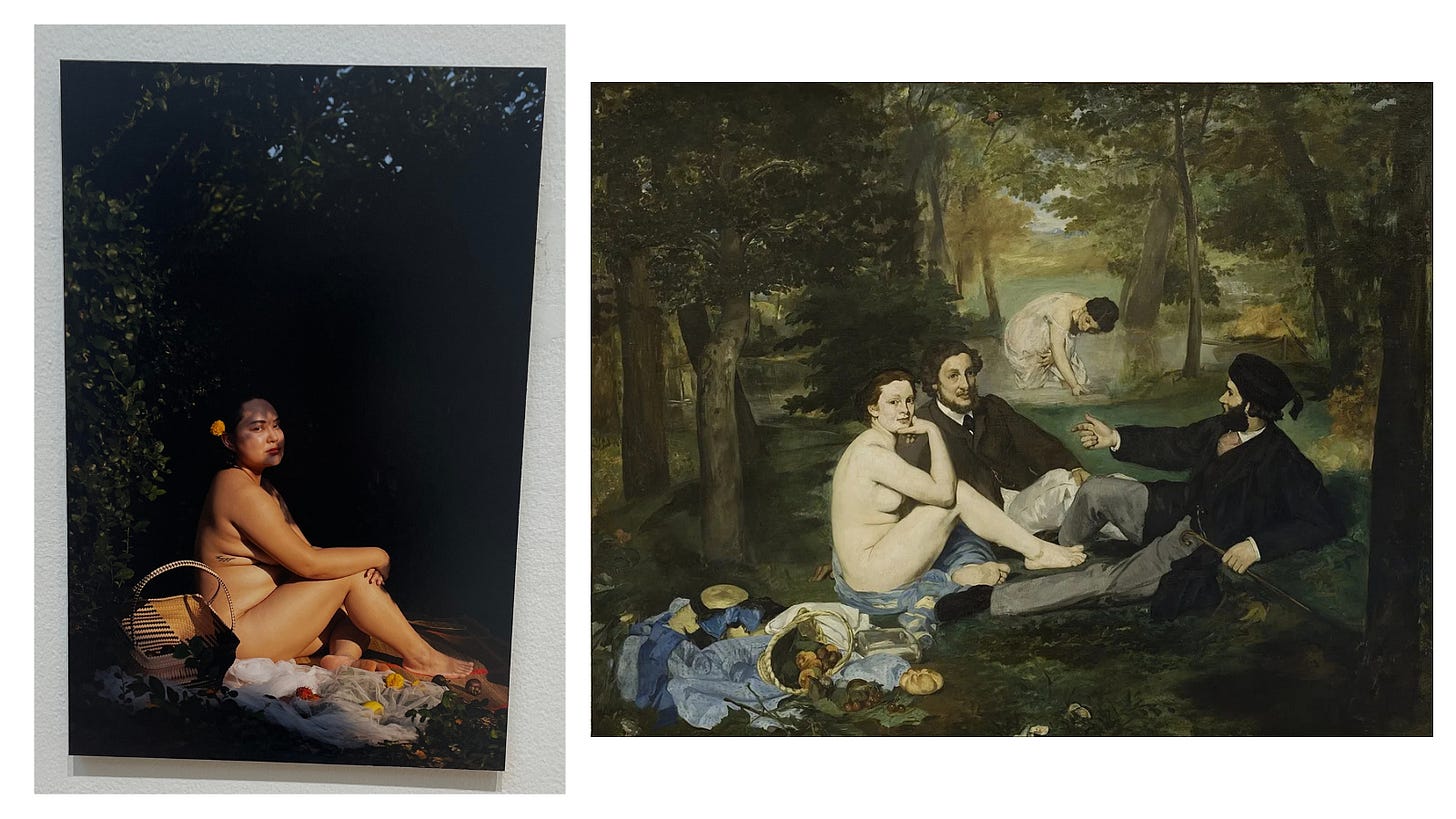

Sophirat Muangkum too got political. She invited us to draw the parallel between the 19 century and the current era. Her photography series Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was the recreation of Edouard Manet painting with the same name. In 1863, Manet's painting drew criticism for his inclusion of woman nudity and possibly sex workers; thus, his painting was rejected from Paris Salon and shown instead at Salon des Refusés (exhibition of rejects).

Last year, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was exhibited as a part of Decentralized Thainess: สลายศูนย์ exhibition at 333Gallery. The thesis of the exhibition, like the name, was to reject the dominant ideology of how Thai people should behave. The work was framed as a rejection of an ideology, and the audience could question the dominant ideology on their own.

At BACC, however her work was framed as political. It was about the lack of rights given by the state. But, Muangkum works were exhibited by the state. Her social issue was already a hot issue in the political landscape. There are multiple activism and think piece.

The two works were political in theme, but they did not do much more than shouting ‘this is an important issue’, which is something society had already know. Maybe the solution is not political speech. Maybe the solution is political action.

It's all about ME ( ˘͈ ᵕ ˘͈♡) by Thavika Savangwongkul was the site specific installation shown at the circular pathway between 8th floor to 9th floor. Visitors walked on the pink carpet. On the wall, the mixture of multiple color splatter paintings, and large selfies of artist were connected together by wall spray graffiti

Her work was not about mother or is explicitly about politics. Instead, it was a way for the artist to share her experience of girlhood performativity. “But what could be more fun than navigating the expectations placed upon her, balancing innocence with the weight of unwritten rules?” Societal pressure on girls to perform femininity had been discussed to death by Judith Butler, but Savangwongkul articulated a new rule to girlhood femininity: "To be a girl is to have fun".

Even though the theme of her piece was not novel, Savangwongkul laid bare her inner emotion, in her graffiti and paintings, for the visitor to examine. Although her work was about her performance specifically, anyone with social media could easily be related.

IV - Conclusion

When I left the museum, I felt sort of empty. Some of the artworks are provocative, but all of them tell the story of what has already been known. A dedicated Mom protects and loves her child. This narrative of a mom is everywhere. I can open TikTok to see Nara Smith cook for her children, or watch literally any TV series. Why go to the museum, if I am not going to encounter a new perspective. Or maybe, I see it. I just didn’t know because the blurb for the artwork is not there.

Nurture Gaia at BACC, Bangkok, from 24 October 2024 to 25 February 2025.

V - Link dump

Love this review from ArtReview. Here a sample:

Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013) – a video critique of ‘the universalist ambition to represent the totality of the world’, as the wall text puts it – comes off like a 13-minute distillation of, or commentary upon, the show at large. Both enlist dissimilar practices and mediums, and both toss references to mythology and science about with abandon.

Janus in Leather Jacket was named one of the best work from Louis Bourgeois. Bangkok Biennale did not provided much detail, but this lot essay from Christie did. The blurb by this work from this work is here.

I felt like it is important to noted that Louise Bourgeois did not considered her art to be feminist art. She did not embrace or reject it. More interestingly, the Feminist Power red was painted in the room that also exhibited palad khinks (a penis shaped amulet that believed to boost sexual power), and a clearly penis shaped lingas. There are some female objects —yonis, Louise Bourgeois sculptures, and Jennie Bringaker sculptures— displayed there as well.

I still do not understand how Nature Study is “dog-goddness”, especially when She-Fox(1985) take almost the exact form. For more detail on Nature Study, Christie lot essay is great

On the website, Amada Heng works is headline “Twenty Years Later”, but in gallery and in the body text on the website it is called Always by my side.

The painting shown on the Bangkok Biennale is called Amamata, the First Mom accroding to aura-asia-art-project.com. It is not shown at BACC.